3 000 years ago… long before the wild boar

According to the legend told by seventeenth and eighteenth century authors, the town was built around a salty spring discovered after a hunting trip wild boar.

“This boar, once pursued, took cover in a muddy place, where he was injured by the hunters. He took flight and went to die in a distant place. It was later tracked down and its corpse was found covered by salt crystals produced during the evaporation of this mud. It was this discovery that gave rise to the town of Salies.”

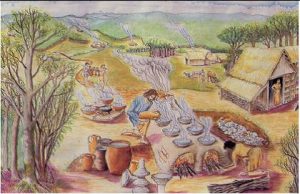

In fact, the origins of the settlement go back to the Bronze Age (which ended five centuries Before Christ), an era when salt was already being extracted by the evaporation of salt water in ceramic pots that have since been dug up by archeologists.

In the Bronze age

At the dawn of Antiquity, a new form of pot appeared.

The evaporation technique seems to have changed with the salt hearth, shown in the picture.

Throughout Antiquity

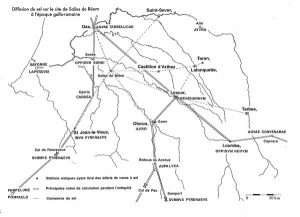

Gradually, men gathered around the Houn Salade, the salty spring from which the precious salty water gushed naturally from the subterranean depths..

Salt was doubtless exchanged for other goods and was taken the length and breadth of the Pyreneean foothills along the old salt road, the Cami Salié, to Toulouse and beyond.

A new production method saw the light of day, according to historians, at the start of the height of the Middle Ages: the use of a metal saltpan. It was much more productive than the short-lived pottery vases used previously: the saltpan allowed salt to be made in larger quantities.

In the Middle Ages

More than any other means of exchange, salt was a truly valuable treasure and was coveted by “foreigners” and sovereigns alike.

Salt has always been a part of survival. It allows meat and dairy foods to be preserved, thus guaranteeing food in difficult time. From this, the South West of France saw the birth of Jambon de Bayonne, potted pork and other regional specialities: air-dried sausages; dry-salted pork bellies; potted duck (confit) as well as Pyreneean cheeses.

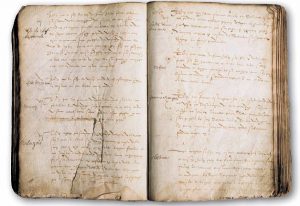

To protect the precious spring, in 1587 the inhabitants of Salies-de-Béarn established the law of the salt spring, the Règlement de la Fontaine Salée, which was set out in the Black Book (le Livre Noir). This law, comprising nine articles, organises the sharing of the salty spring water between neighbours (“les voisins”). It established the rights to land and inheritance; the water may only be drawn by families from Salies-de-Béarn and these rights may only be transmitted from one generation to the next under certain conditions.

Download the Règlement de la Fontaine Salée of 1587 (in old French) (PDF file)

Even after more than four centuries, this is still the law that rules the sharing of revenues drawn from the salt water spring and the inheritance rights of this collective property from which the descendents of the 16th century denizens of Salies-de-Béarn make a living. These stakeholders are referred to as the “Parts Prenants”.

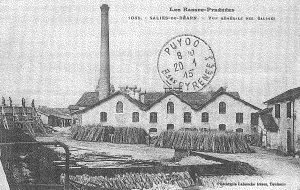

Until the 19th century, water from the Fontaine Salée was exploited by small saltmakers. The Salt Law of June 1, 1840 imposed a requirement that only saltworks producing more than 500 tonnes a year should be retained. So it was that the Saltworks of Salies-de-Béarn came to be built in 1842, on the site of what is now the Pavillon Saleys. The factory scaled up the production methods that had been used previously by traditional saltmakers.

Au XIXe siècle

Following a fire in 1888, the original saltworks was replace by a second saltworks, built in the Herre quartier, where it is still working today.

It has been renovated several times since then and uses a number of advanced technologies: wood-fired heating fuelled from surrounding woodland; heat recovery and electric heating.

Salies-de-Béarn, ville thermale

In the 19th century, Salies-de-Béarn Salt faces competition from cheaper sea salt. Having proved the curative effects of the salt-rich waters of Salies-de-Béarn to their satisfaction, the Parts Prenants were encouraged to explore the potential of setting up a thermal spa to add value to their unique water. In 1857, the Academy of Medicine authorises the use of saltwater from the spring at Bayaà for therapeutic uses. In 1891, this authorisation is extended to the Reine Jeanne d’Oraàs saltwater spring.

Despite having been planned since 1853, it was 1857 before the first thermal establishment was built within the walls of the saltworks. It was designed to allow the simultaneous production of food grade salt, thermal spring waters and mother liquors (the insoluble muds remaining after evaporation of the dissolved salts) used for the thermal baths. The therapeutic benefits are numerous. Doctor Jean-Brice Coustalé de Larroque, the physician to the emperor Napoleon III, attracted a well-to-do Parisian clientele. In this way, he boosted the reputation of the thermal spa.

During the 19th century, Salies-de-Béarn benefitted from the arrival of a new form of medicine: taking the waters. “Salies-de-Béarn, health through salt” was the slogan that was to be found on posters in the Paris metro in the early years of the 20th century.

Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité

The banner for the saltmakers’ community is a piece of regalia still housed by the stakeholders in the salt spring, the Parts-Prenants. It was given to the community by Madame Combes-Saint-Macary in 1900. This lady, the owner of the château Bijou de Labastide-Villefranche, both wove and embroidered this banner in gold thread to replace a previous banner.

The symbols used

- The long pole is the sign of authority and sharing..

- The wooden brine bucket containing salt water shows the local wealth. It also symbolises fair shares.

- The boar appears alive, representing the necessary independence for survival.

- The Maltese cross is a witness to the origins of the organisation.

- The four basque crosses in each corner of the banner signify the passage of the four seasons, as well as a universal symbol of live and tolerance.

FRA

FRA DEU

DEU ESP

ESP JPN

JPN